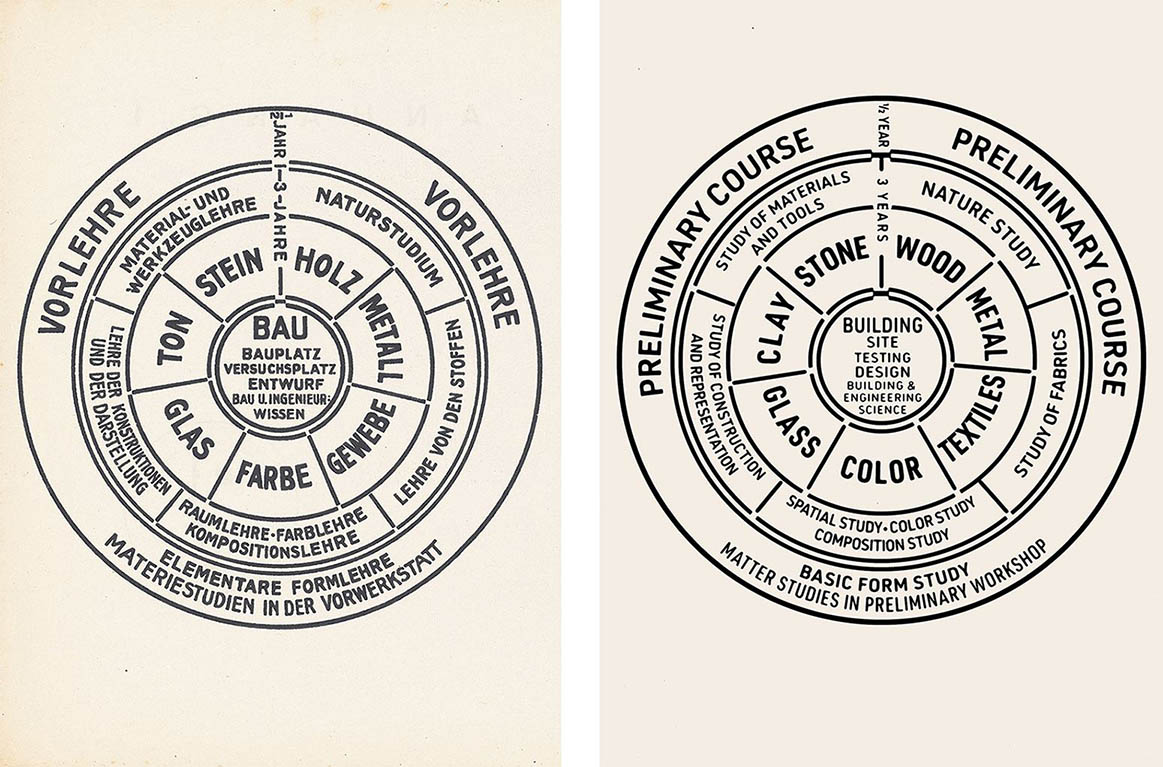

Josef Albers, who was born in Bottrop on March 19, 1888, worked as an elementary school teacher before training as an art teacher in Berlin until 1951. He then studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule Essen, where he was a student of the artist Jan Thorn Prikker, known for his stained glass windows. Albers then continued his studies at the Königlich Bayerische Kunstakademie in Munich before joining the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1920. During his first years at the Bauhaus, Albers was primarily concerned with glass painting and became the technical director of the glass workshop at the Bauhaus as early as 1922, just two years after beginning his studies. From 1923 Albers taught as a junior master, and from 1925 as a Bauhaus master. In the same year, the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, where Albers became deputy to Bauhaus director Mies van der Rohe.

After the Nazis closed the Bauhaus in 1933, Albers and his wife Anni Albers moved to the United States, where he taught from then on at Black Mountain College, an art school in North Carolina. He also designed the logo for Black Mountain College. From 1950 until his retirement in 1959, Albers headed the Design Department at Yale University.

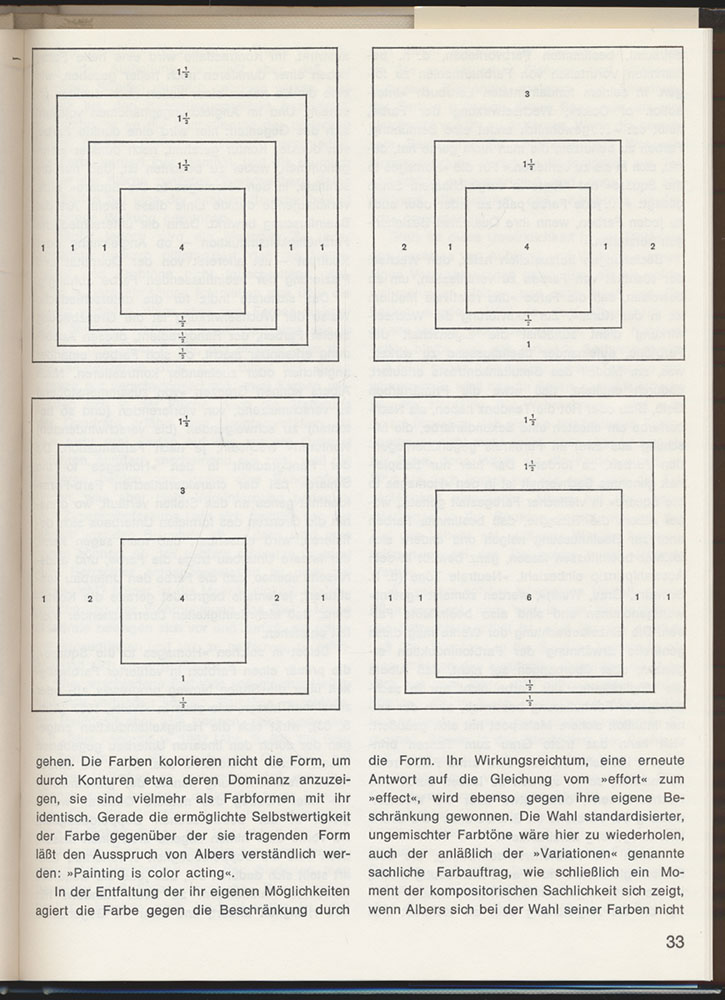

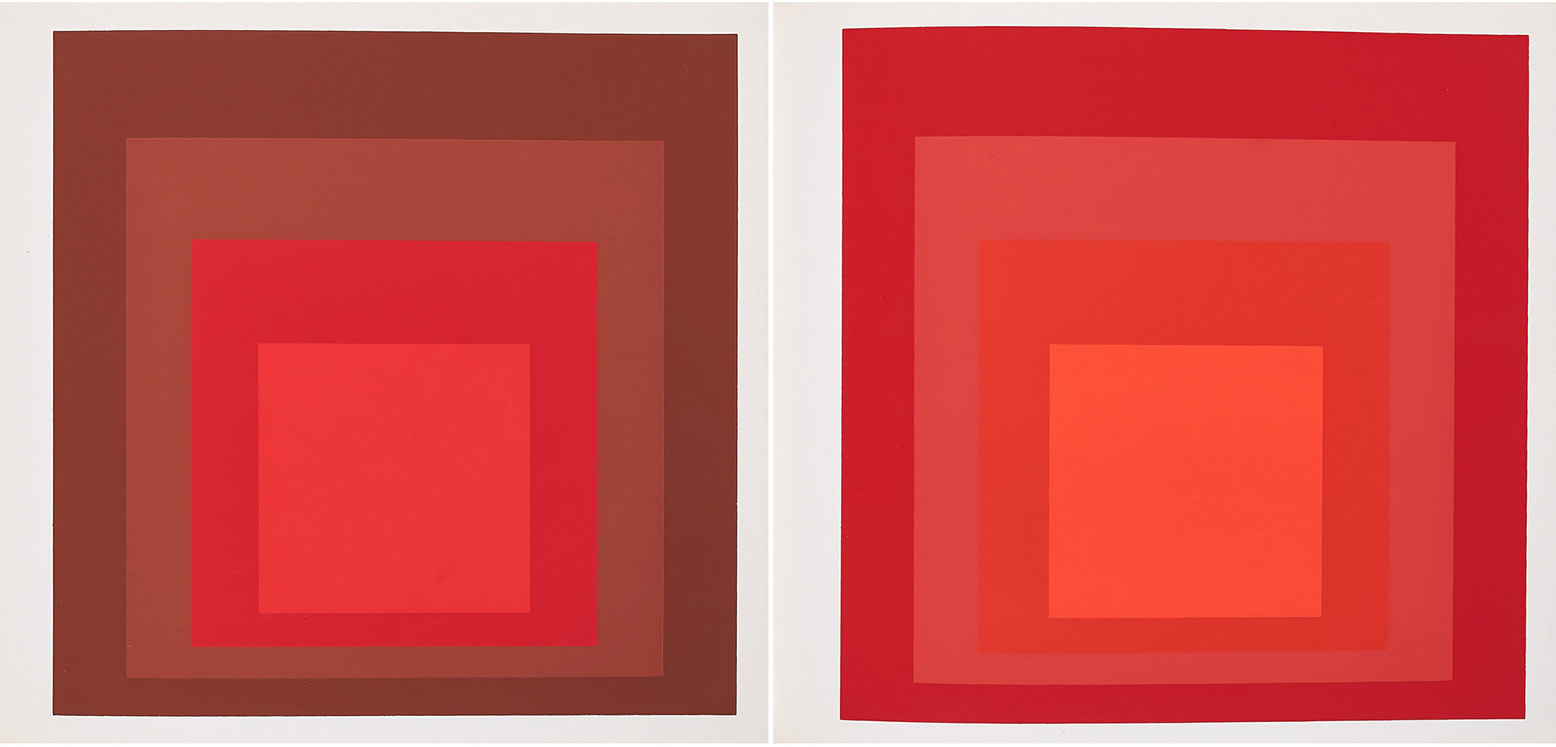

Albers' best-known work as a painter is the series of quadratic paintings titled Homage to the Square, which he made in over 2000 variations from 1950 until his death in 1976.↓[1] The paintings were created in different dimensions, but the basic principle always remained the same. Three to four squares are staggered within each other, with the inner squares not aligned with the center but tending downward, creating larger stripes in the upper part of the painting and smaller stripes in the lower part.↓[2]

In Homage to the Square, Albers explores optical perception and the interplay of colors in various constellations, as well as the different color phenomena. Albers chose the square as his initial form because he was aiming for "the least possible effort, the restriction to the geometric element."↓[3] Albers was also interested in the geometry of the square. Already at the Bauhaus

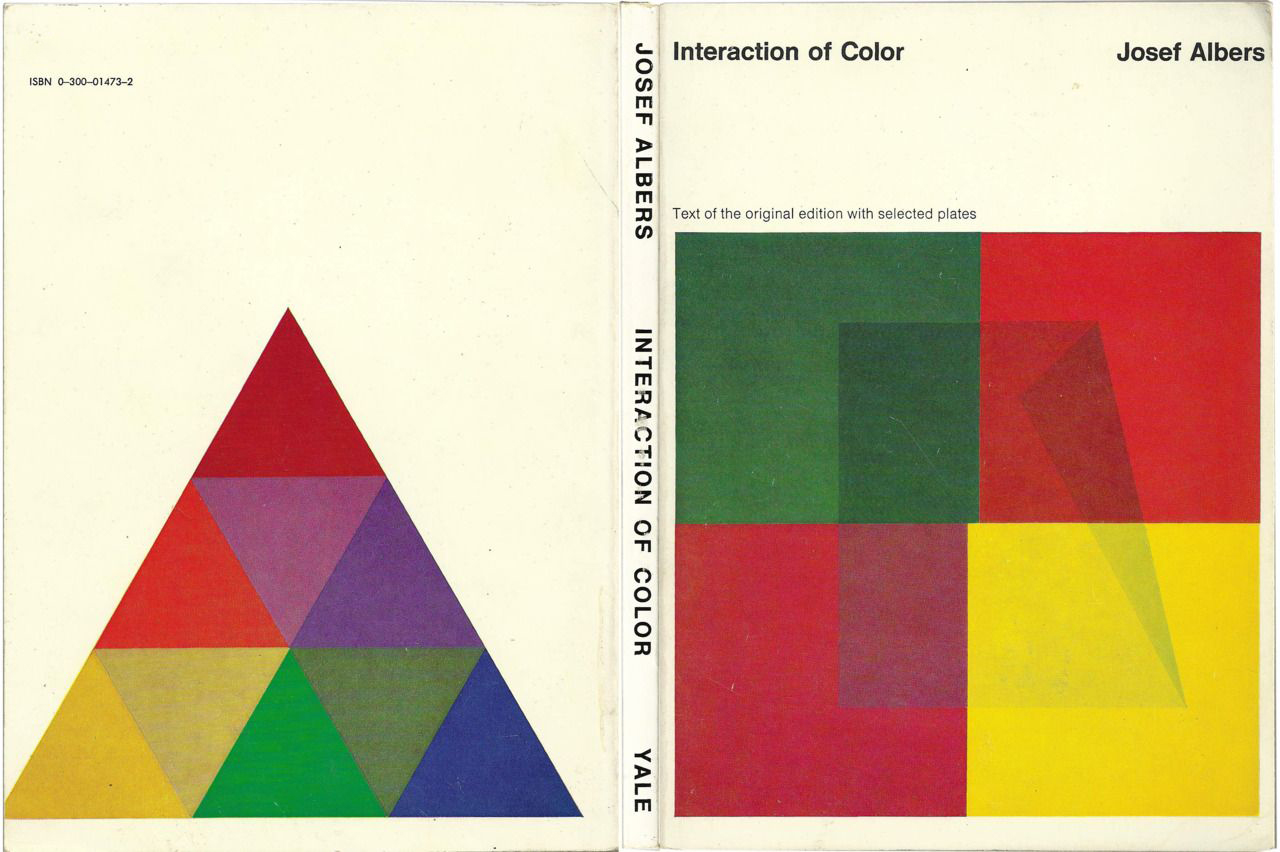

Albers taught his students to optimize the relationship between "effort" and "effect" under the concept of "economy of means."↓[4] Although Albers' choice of the square as a pictorial object places him in the tradition of Modernism with artists such as Malevich or Mondrian, he is considered a precursor of Hard Edge painting and, through his serial method of working, also a pioneer of Minimal Art. Through his exploration of visual perception, he also became, along with Victor Vasarely, the most important pioneer of Op Art. Albers himself justified working in series by saying that "there is not just one solution to an aesthetic problem."↓[5] For the paintings in the Homage to the Square series, Albers used only industrially produced paints, the exact name of which he noted on the back of each painting. Although the concept of three or four interlocking squares appears rigid at first glance, the extraordinary complexity of the work becomes apparent when viewing different variations. Albers uses the simple initial form to depict the nearly infinite color relationships and interactions of the colors. In his 1963 book on color theory, Interaction of Color, Albers writes in the introduction, "In visual perception a color is almost never seen as it really is - as it physically is. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art. In order to use color effectively it is necessary to recognize that color deceives continually." In Homage to the Square, Albers highlights the contrast between the physical materiality of color and the subjective perception of color. In each painting, he chose colors based on their interaction and relationship to each other.

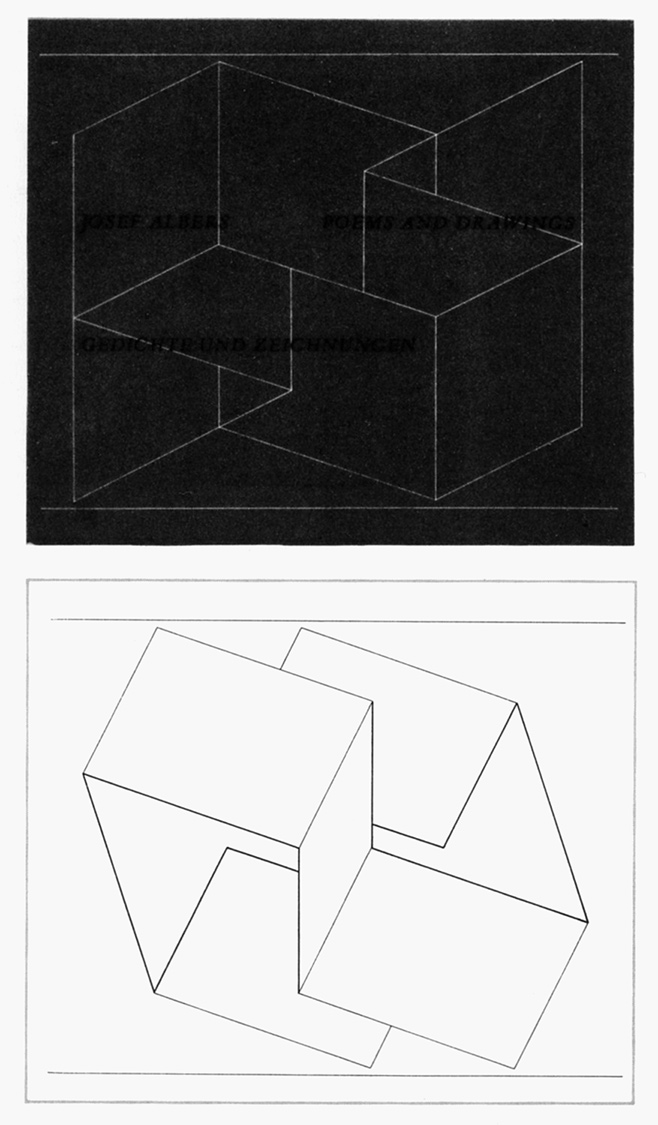

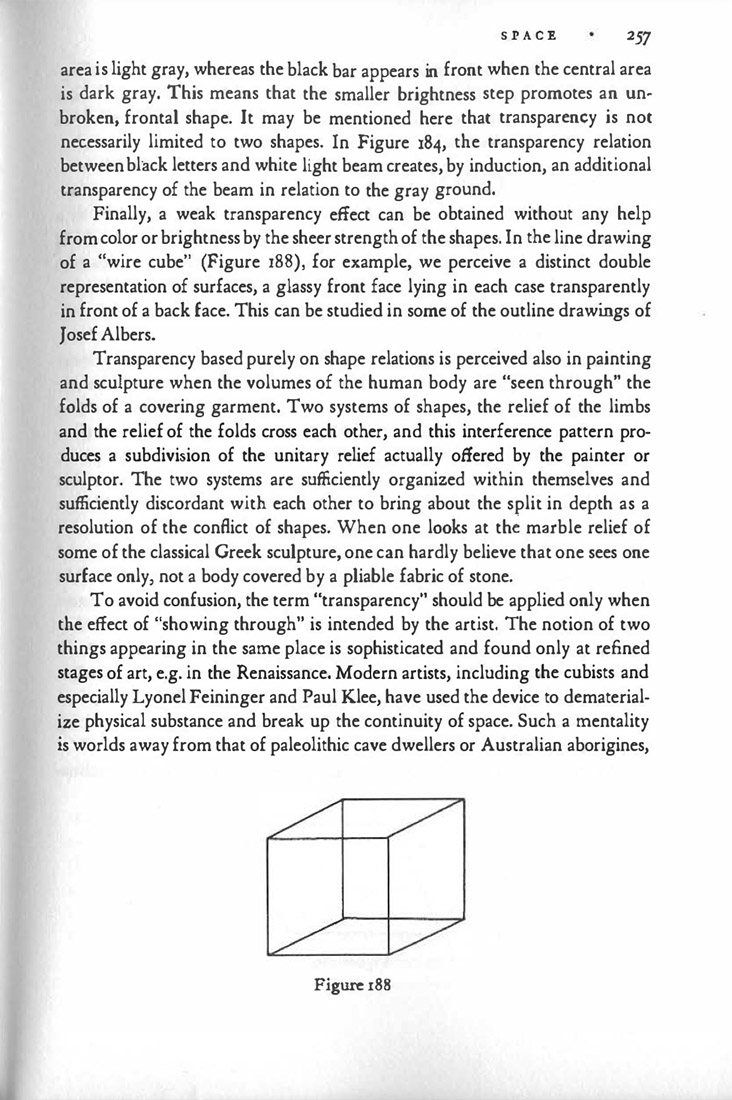

However, he was not solely concerned with color perception. He also pursued socio-political goals with his painting. Albers wrote about this: "Color - just like man - follows two different modes of behavior. First, self-realization and then the relationship to others. In my paintings I have tried to combine two polarities - independence and interdependence. In other words, one must be able to be an individual and a member of society at the same time. That's the parallel."↓[6] In the works of the Structural Constellations series, which Albers began in the 1950s, he experimented with visual ambiguity in the perception of spatial structures on the two-dimensional surface in the form of drawings and prints. Albers always emphasized his concern as a teacher and as an artist was to "open the eyes" of students or viewers. At first glance, narrow lines form simple geometric figures in Structural Constellations. Upon closer inspection, however, it becomes clear that the images cannot be interpreted visually in only one way. Because Albers' use of parallel perspective in these drawings gives the illusory impression of spatiality, but prevents him from showing depth features of the geometric figures, the images can be interpreted spatially in different ways.

In Gestalt psychology, this effect is called multistable perception. Rudolf Arnheim explains this phenomenon in his 1954 book Art and Visual Perception, in which Gestalt psychology is applied to art for the first time, using the example of Albers Structural Constellations with the Necker Cube.

Similar to Homage to the Square, Albers achieves a strong visual impact with minimal means. He himself spoke of "minimum means for maximum effect" in connection with his artistic works.↓[7] For his Structural Constellations, Albers dispensed entirely with color and worked exclusively in black and white, rarely in gray. This brings the examination of the line, the surface, and the resulting space into the foreground. With these drawings, which at first glance seem so transparent, Albers questioned spatial perception, much as he questioned the permanence of color perception with his paintings for Homage to the Square. As an artist, Albers had a major influence on the development of American painting. His work is usually classified as concrete art, but he is considered to have paved the way for many later art movements through his exploration of colors, shapes, lines, surfaces, and their interactions on both cognitive and subjective visual perception. In 1968, for example, Albers participated in the famous Op Art exhibition The Responsive Eye at MoMA and was described in the catalog by the exhibition's curator, William C. Seitz, as a "master of abstraction."

As a teacher, Albers also exerted great influence on the artistic development of the second half of the 20th century. After the Bauhaus in Germany was closed under Nazi pressure, Albers and his wife Anni Albers accepted an invitation to Black Mountain College, where he integrated many of the principles of the Bauhaus preliminary course he had previously led and taught renowned artists such as Donald Judd, Cy Twombly, and Robert Rauschenberg.

At Yale University, where he became head of the Design Department in 1950, he also taught many later famous artists such as Eva Hesse and Richard Serra. He also took on numerous guest lectureships; in 1965, for example, he gave three lectures at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. The lectures, which were among his last public lectures, were published in a book designed by graphic design legend Norman Ives, appropriately titled Search versus Re-Search for Alber's artistic approach.

In 1954 and 1955, Albers also lectured as a visiting professor at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany, founded by Max Bill and modeled on the teaching methods of the Bauhaus. Albers' most important theoretical work is considered to be the book Interaction of Color, published by Yale University Press in 1963, in which he recorded the results of his decades of research into the effects of color and form.

NOTES

[1] Heinz Liesbrock, Josef Albers Interaction Katalog, Villa Hügel, Essen, 2018

[2] Rainer Wick, Kunsthochschule der Moderne, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2000, p. 165

[3] Jürgen Wießmann, Josef Albers, 1971

[4] Wick, 2000, p. 165

[5] Wießmann, 1971

[6] zeit.de [↗]

[7] Wießmann, 1971