After Sol LeWitt completed his art studies at Syracuse University in New York in 1949, he initially earned his living as a graphic designer for the architect Ieoh Ming Pei. At this point, LeWitt still considered himself a painter and worked in an abstract expressionist style.

From 1960 to 1965 he worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he met the artists Dan Flavin, Robert Ryman and Robert Mangold, who were also employed there and who had a strong influence on LeWitt's artistic development. Between 1962 and 1963 he created his first geometric and monochrome works, the "Wall Structures". The wooden wall objects range between the fields of painting, sculpture, and relief.↓[1]

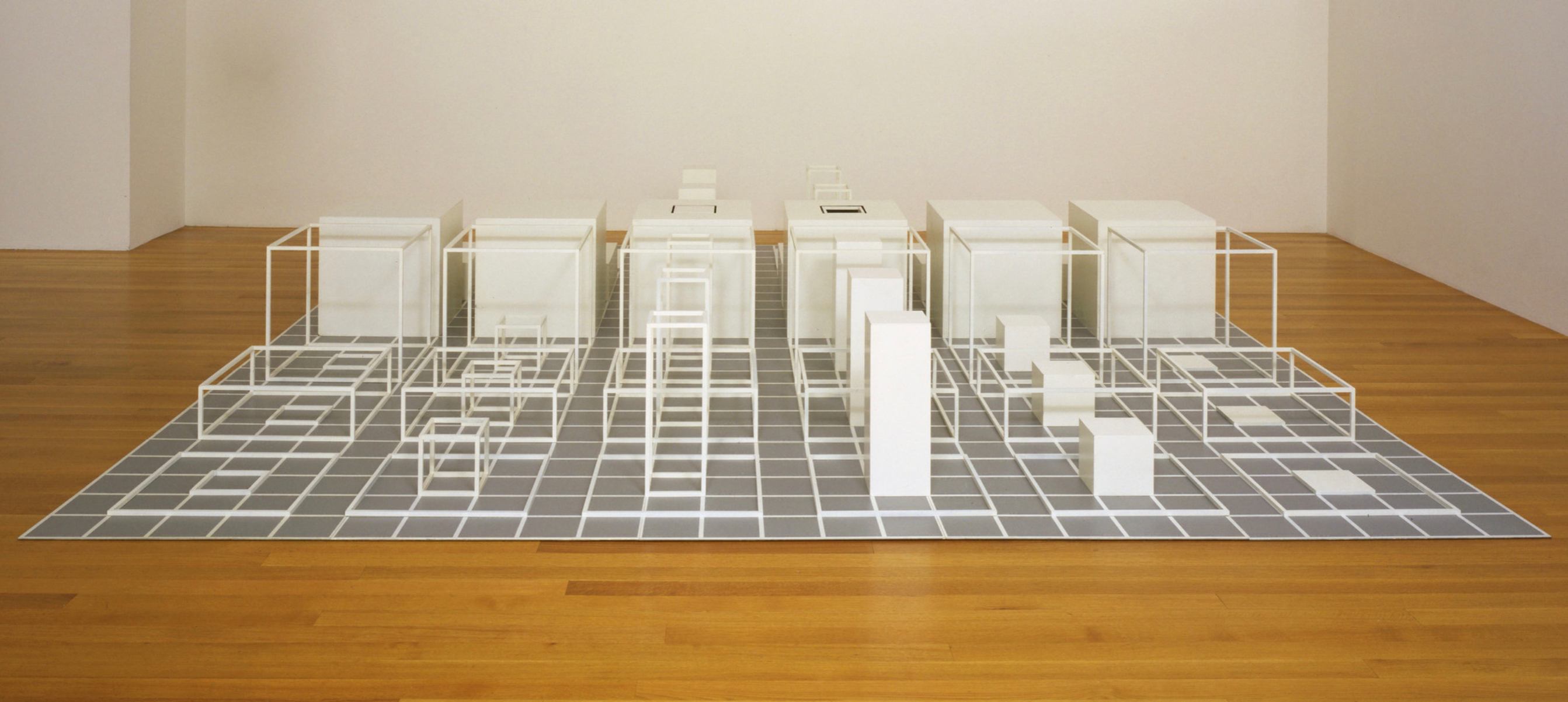

A decisive turning point for LeWitt's artistic work took place in 1966 with the work "Serial Project No. 1 (ABCD)." The work was industrially produced according to LeWitt's instructions and consists of various combinations of open and closed cubes, as well as squares lying flat, arranged on a grid measuring just under 4x4m. The variations depicted show all the "relevant" (according to LeWitt) combinations of closed and open cubes and squares, which in turn contain open or closed cubes and squares.↓[2]

In a text published in 1966 together with the work "Serial Project No.1 (ABCD), Sol LeWitt writes: "The aim of the artist would not be to instruct the viewer but to give him information. Whether the viewer understands this information is incidental to the artist; he cannot force the understanding of all his viewers. He would follow his predetermined premise to its conclusion avoiding subjectivity. Chance, taste, or unconsciously remembered forms would play no part in the outcome. The serial artist does not attempt to produce a beautiful or mysterious object but functions merely as a clerk cataloging the results of his premise."↓[3]

"Serial Project No.1 (ABCD)" is the first of a large number of LeWitt's serial conceptual works, whose initial form is the cube. The sculptures, which are exclusively industrially produced and made of steel or aluminum, are always painted white, and the idea or concept is the primary focus of the works. LeWitt, who at the time was usually assigned to Minimal Art by critics, although he rejected this term himself, leaves Minimal Art behind with this step towards serial and conceptual art.↓[4]

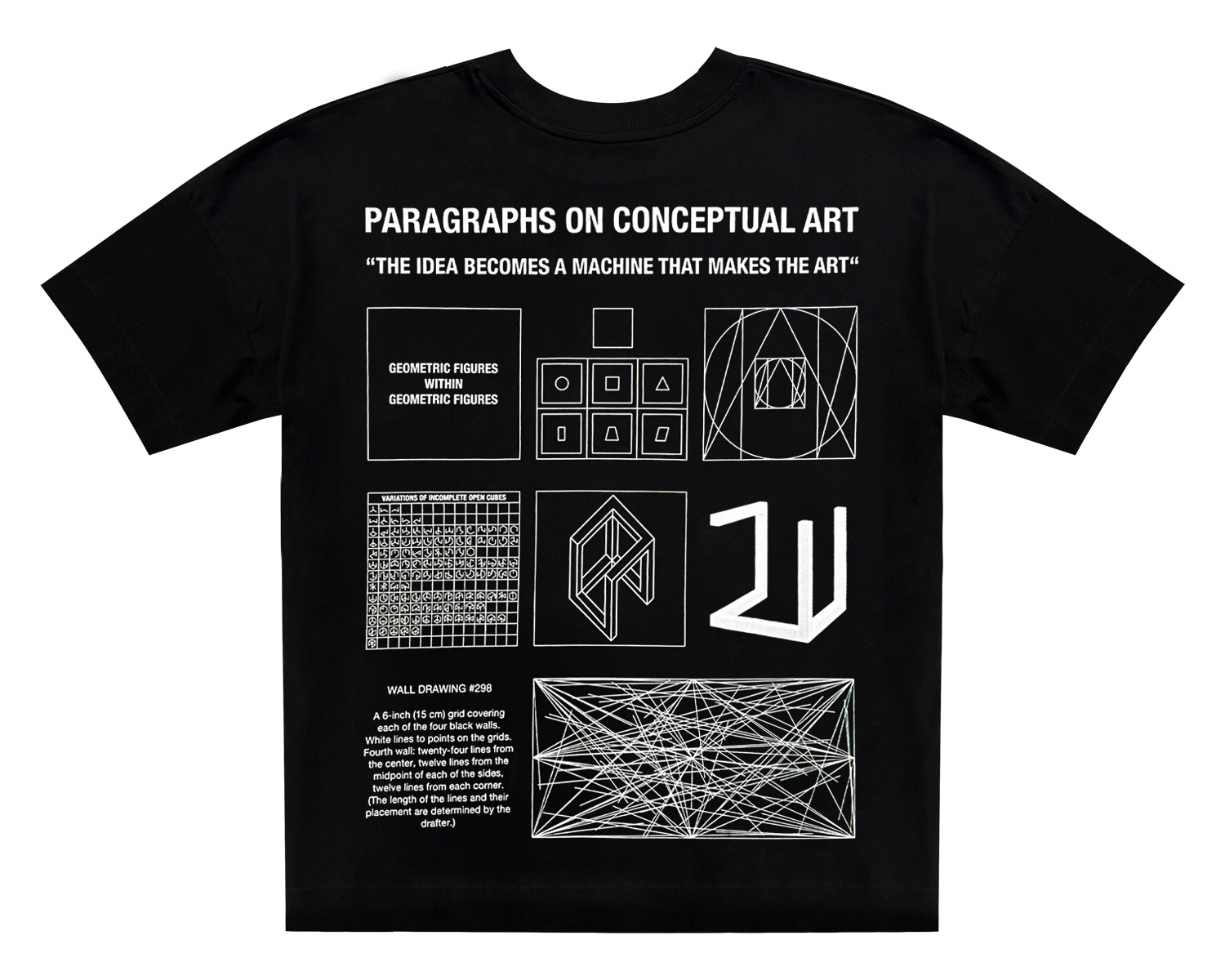

Not least thanks to his manifesto "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art," published in 1967 by Art Forum, LeWitt became a pioneer of conceptual art. In the manifesto he explains that in "conceptual art" the idea or concept of a work of art is more important than the materially existing work of art. However, the idea does not necessarily have to be complicated or logical. The artworks were primarily intellectually interesting to the viewer, in contrast to "perceptual art," which was primarily visually interesting to the viewer.↓[5]

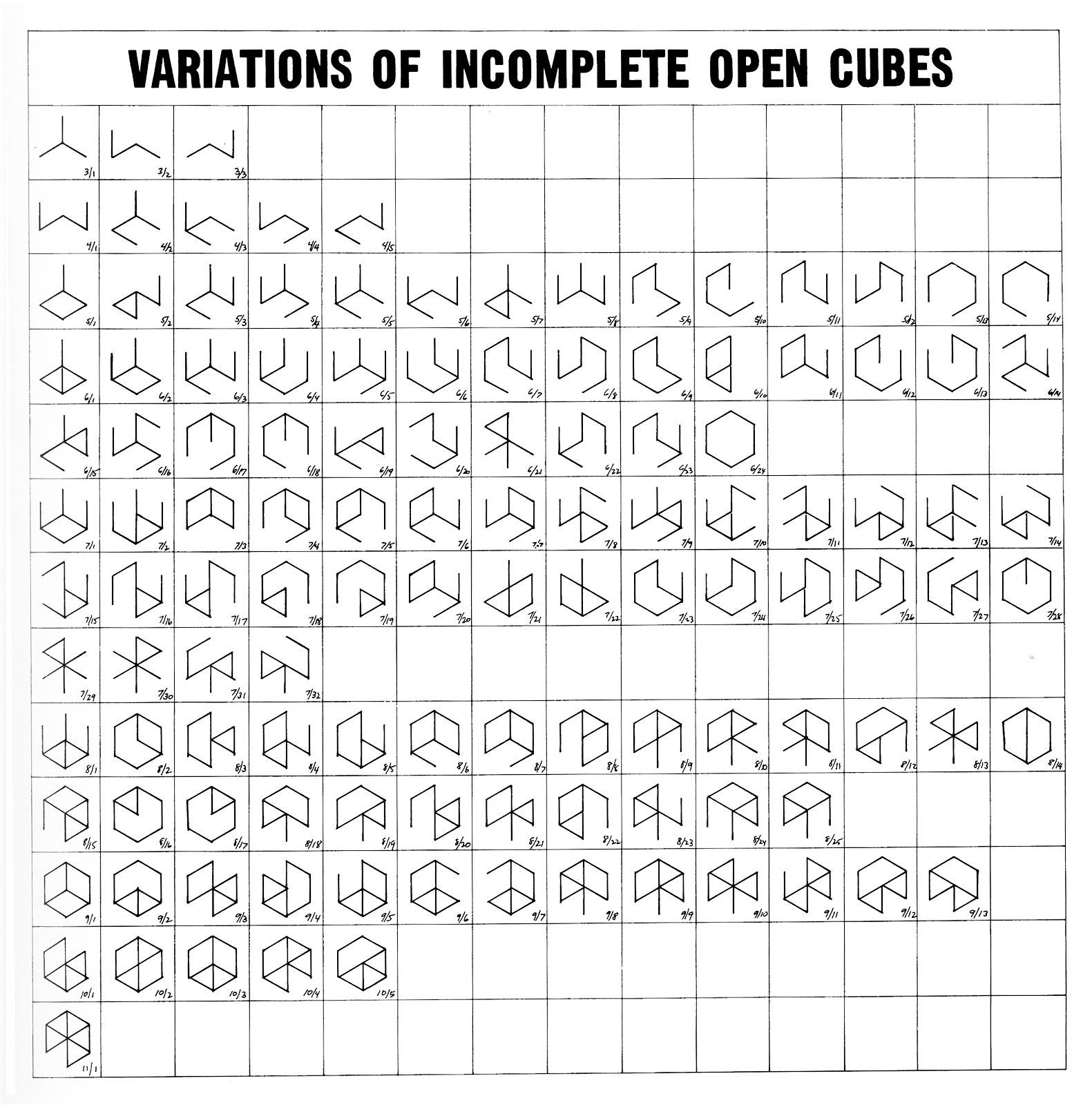

Among LeWitt's best-known conceptual works is "Variations Incomplete Open Cubes," a serial work consisting of 122 different variations of cubes with at least one edge missing. LeWitt defined the following rules for "Incomplete Open Cubes": Each valid variation must be three-dimensional (at least three edges must be present); the structure must be contiguous; two variations are considered different if they differ by a reflection, but identical if they differ by a rotation. This concept was implemented by LeWitt in a variety of different media and scales. In addition to the well-known white-painted aluminum sculptures, drawings, photographs, artist books, and smaller wooden models have also been created.

The translation of the same concept into different media and scales is an important aspect of LeWitt's conceptual way of working. For him, sketches, notes, and models are also equal to the realized work. LeWitt's conceptual working method is evident, among other things, in the fact that his structures (LeWitt preferred the term "structures" instead of "sculptures" for his spatial works) are industrially produced. Intervention by the artist himself is not necessary in the realization of the artwork, as the concept is superior to the realized work. The Incomplete Open Cubes made of aluminum (formerly also made of steel or wood) are painted white, so that visually no conclusion can be drawn about the material. LeWitt's famous quote "the idea becomes the machine that makes the art."↓[6] is made evident by this work. Starting from a relatively simple idea, a multitude of different works emerge.

Although the concept follows a self-contained logic, the premise of the concept seems irrational. For LeWitt, however, this is not a contradiction. He wrote, "Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically." The text Sentences on conceptual art, from which this quote is taken, appeared in May 1969 in the first issue of the publication Art-Language by the artist group Art & Language. In the text, LeWitt expanded on his position on conceptual art in 35 short sentences.

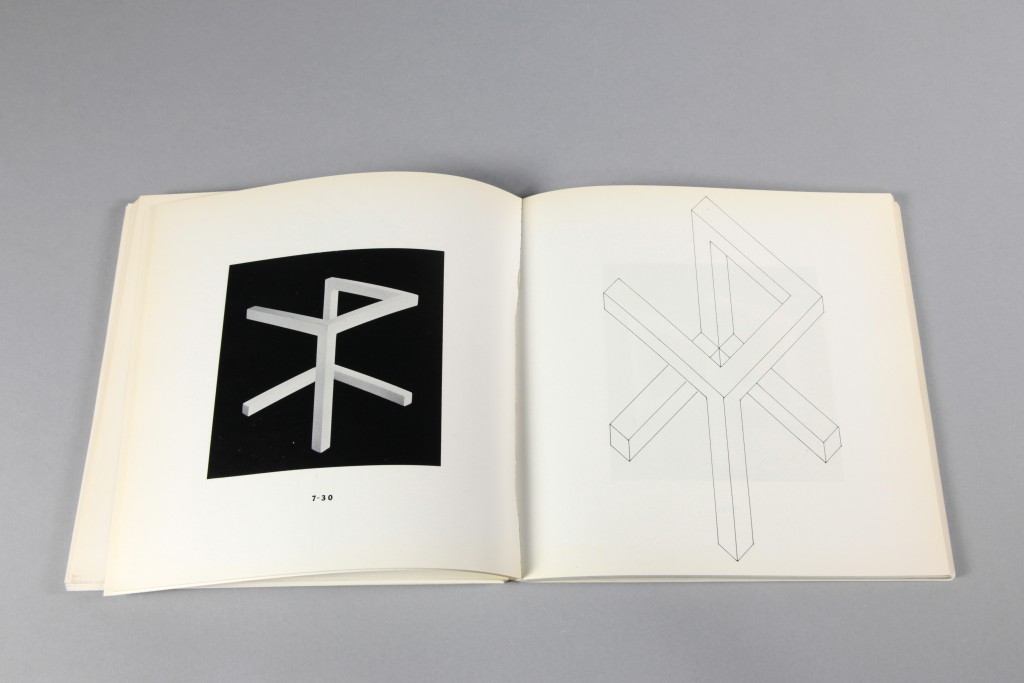

In the artist's book for "Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes" with the same title, photographs of all 122 sculptures are shown against a black background. Each photograph is juxtaposed with the corresponding technical drawing. The book was considered by LeWitt to be as much a work of art as the sculptures depicted in the book.

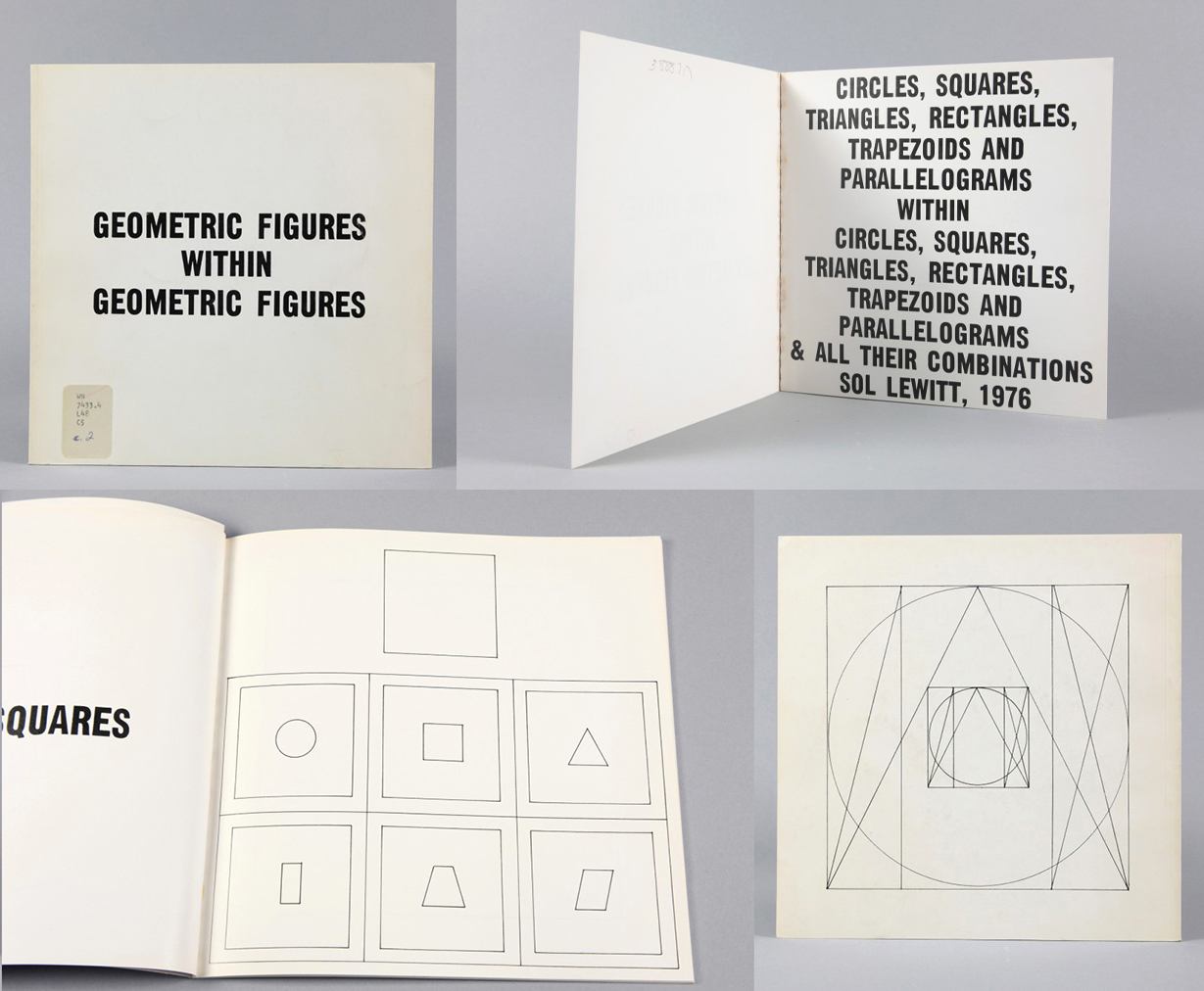

Between 1967 and 2002, LeWitt produced over 80 artist books. In 1976 LeWitt also founded the publishing house "Printed Matter" together with the art theorist and curator Lucy R. Lippard for the publication of artists' books. The term artist's book should not be understood as a book about the artist or a book about art, but rather refers to the book itself as an art form that LeWitt used to expand his artistic practice. Often the books are named after the instructions that are the basis for the works shown, as in the case of the book "Four basic Kinds of straight lines: 1. Vertical. 2. Horizontal 3. Diagonal l.[eft] to r.[ight] 4. Diagonal r.[ight] to l.[eft] And their combinations", or "Geometric Figures within Geometric Figures. Circles, squares, triangles, rectangles, trapezoids and parallelograms : within circles, squares, triangles, rectangles, trapezoids and parallelograms & all their combinations". The title of the book already describes the concept, which is presented in the book in all its possible combinations.

In addition to his sculptural works, LeWitt is particularly known for his Wall Drawings, of which he conceived over 1200 variations between 1968 and 2007. LeWitt produced the first Wall Drawing himself in 1968 at the Paula Cooper Gallery in New York; later he only developed the concepts, which were then realized by assistants.

The diversity of the Wall Drawings becomes apparent through LeWitt's use of a wide variety of media, as well as through the continuous expansion of his repertoire of forms. Initially, he worked primarily with lines, later also with simple geometric figures, and towards the end of his creative period also with more complex and less strict figures and forms, which he himself described as "continuous forms". LeWitt compared himself in his role for the Wall Drawings, whose concepts he created but did not execute himself, to that of a composer who writes a piece of music that can be played by various musicians, although the intellectual property always remains with the artist or the composer. The concept, or the piece of music, will always remain the same, but the execution will change slightly each time.↓[7]The "Wall Drawings" make LeWitt's central idea that the concept is superior to the realized work particularly visible. Since the Wall Drawings are executed directly on the wall, a buyer receives a certificate about the respective work instead of a work of art as such. Such a certificate usually consists of a diagram and instructions on how to execute the work. The purchase of a certificate entitles the owner to have the respective "Wall Drawing" reconstructed on any wall.

The early Wall Drawings consist of the various ways of representing a straight line: vertically; horizontally; diagonally from left to right; diagonally from right to left and the various ways of combining them. For the first Wall Drawing, LeWitt drew 32 squares of equal size, showing all the ways each of two of the four possible ways of combining straight lines.

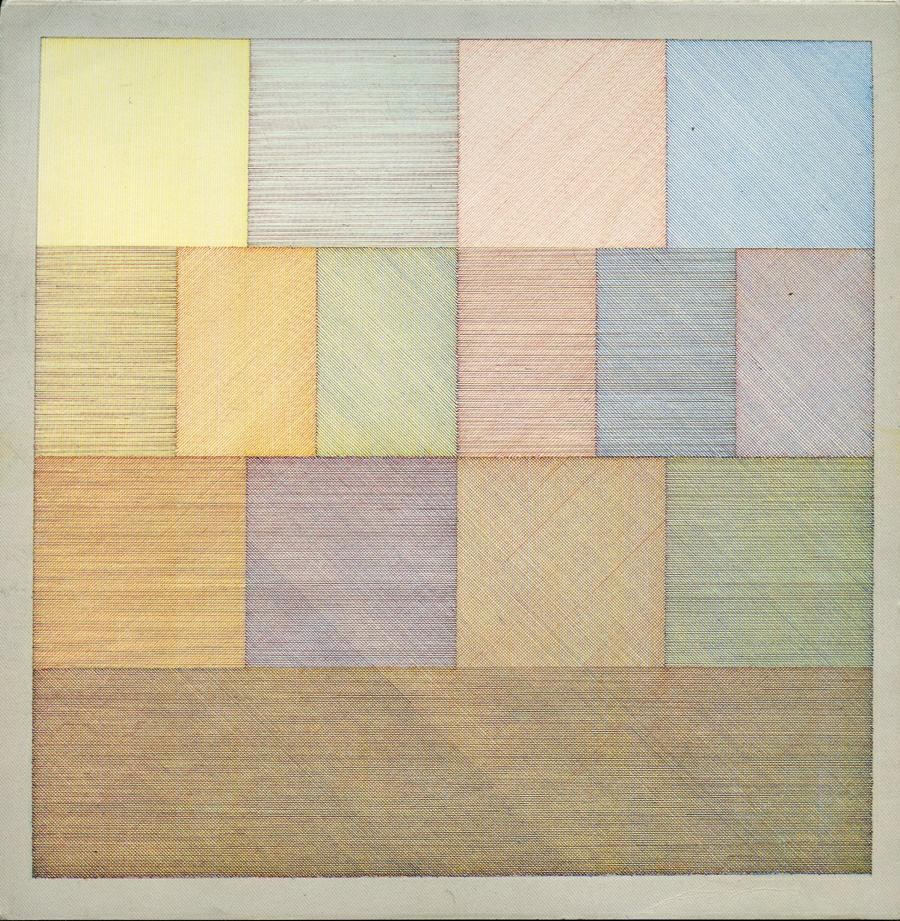

Later Wall Drawings were often realized with colored chalk or crayons, using the primary colors blue, red, and yellow for one type of line each. For example, in "Wall Drawing #85," a wall is divided into four equal parts. The first row consists of four equal parts, each of which has one type of line in an assigned color, yellow, blue, red or black. In the second row, consisting of six equal-sized parts, two of each color and line are combined. In the third row, consisting of four equal parts, three colors and lines are combined each, and in the last row all combinations are superimposed.

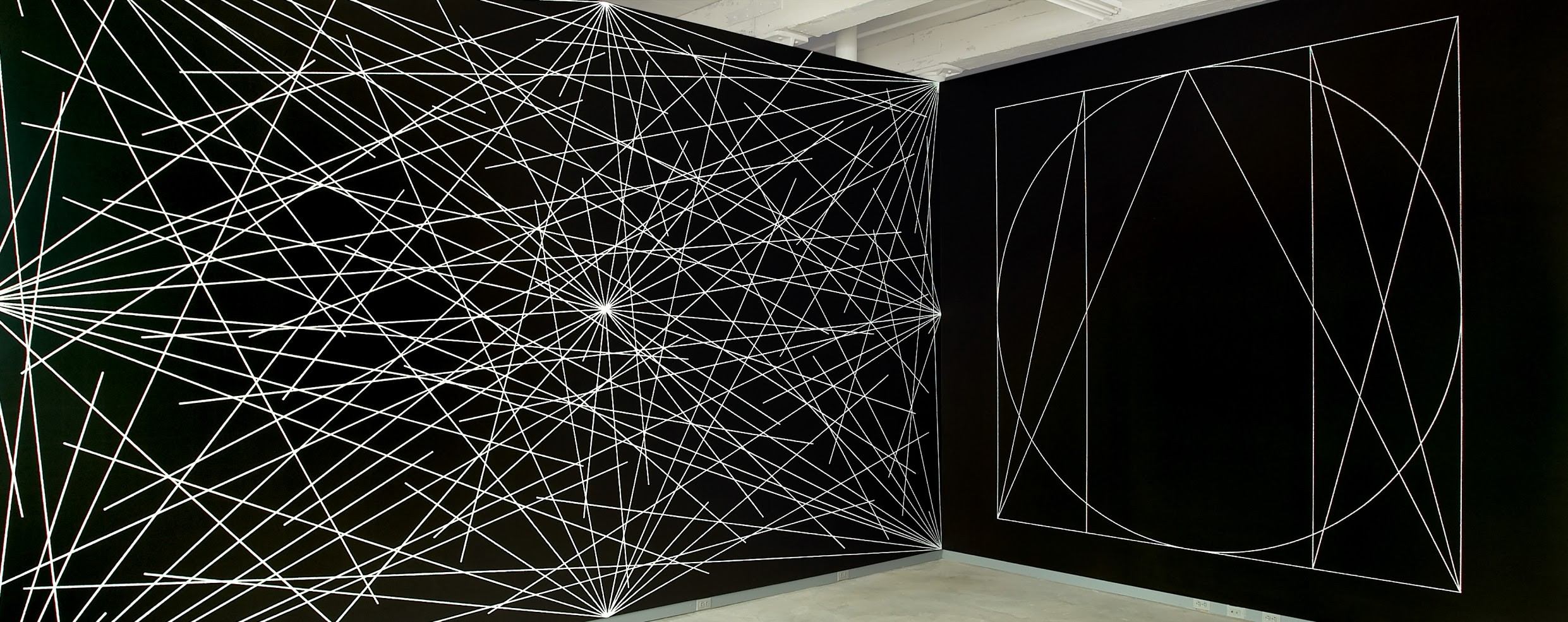

Later, LeWitt expanded his repertoire and no longer limited himself to depicting the various types of straight lines. This resulted in works such as "Wall Drawing #289," whose instruction: "A 6-inch (15 cm) grid covering each of the four black walls. White lines to points on the grids. Fourth wall: twenty-four lines from the center, twelve lines from the midpoint of each of the sides, twelve lines from each corner. (The length of the lines and their placement are determined by the drafter.)". This type of wall drawing introduces a new aspect into LeWitt's artistic work, as the draftsman is given a certain amount of freedom in the realization of the work.

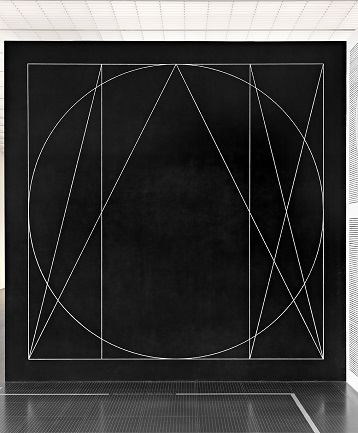

In the 1970s, LeWitt again expanded his repertoire of forms and integrated geometric shapes. These were initially limited to primary forms, which he defined as the circle, square, and triangle, but he soon added secondary forms such as the rectangle, trapezoid, and parallelogram. These six (later nine) geometric shapes are used repeatedly in LeWitt's wall drawings (and other works such as the aforementioned book Geometric Figures within Geometric Figures) from then on, such as in Wall Drawing #295. The instruction for this wall drawing reads, "Six white geometric figures (outlines) superimposed on a black wall." In addition to the geometric shapes, superimposition, which LeWitt already used in his early Wall Drawings to expand the possible combinations of straight lines, is also employed here. The primary and secondary shapes defined by LeWitt are superimposed within the square, revealing structural commonalities between the shapes.↓[8]

In the 1990s, LeWitt also began to integrate irregular, organic forms into his wall drawings, thus expanding his repertoire of forms once again. LeWitt also expanded his color palette. This was initially limited to black and the primary colors yellow, red, and blue. In the 1990s, he expanded this to include secondary colors such as orange, violet, and green. In "Wall Drawing #901" from 1999 with the instruction: "Color bands and black blob. The wall is divided vertically into six equal bands; red; yellow; blue; orange; purple; green. In the center is a black glossy blob." Is an organic black shape, called a "blob" by LeWitt, reminiscent of comic books painted over six equal-width bands of red, yellow, blue, orange, purple, and green.↓[9]

Although this Wall Drawing, like most of the Wall Drawings created in the late 1990s, was executed with acrylic paint, LeWitt continues to title his works as Wall "Drawings" rather than murals, emphasizing the integration of these works into the strictly intellectual overall concept of his oeuvre.↓[10]

NOTES

[1] cf. Daniel Marzona, Minimal Art, Taschen, p. 19

[2] cf. ibid., p. 20–21

[3] Sol LeWitt, Serial Project #1, Aspen Magazine No. 5+6, 1967

[4] cf. Marzona, pS. 20–21

[5] cf. Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, Art Forum, 1967

[6] ibid.

[7] cf. MoMA Press Release, Sol LeWitts Wall Drawing #564, 2013

[8] MASS MoCA [↗]

[9] MASS MoCA [↗]

[10] MASS MoCA [↗]